The vastness of Dinétah (the Diné homeland) is rich with the narratives that exist within the landscape. The Diné holds a close relationship to our home, and each area has sacred significance and places of stories. Diné visit these places to connect to our ancestors and connect with the powers of the land. Through these interrelated places, we never forget that we exist within a larger story, one that is part of a much larger living system that includes the water, earth, canyons, and plants. It is through these places that healing can begin.

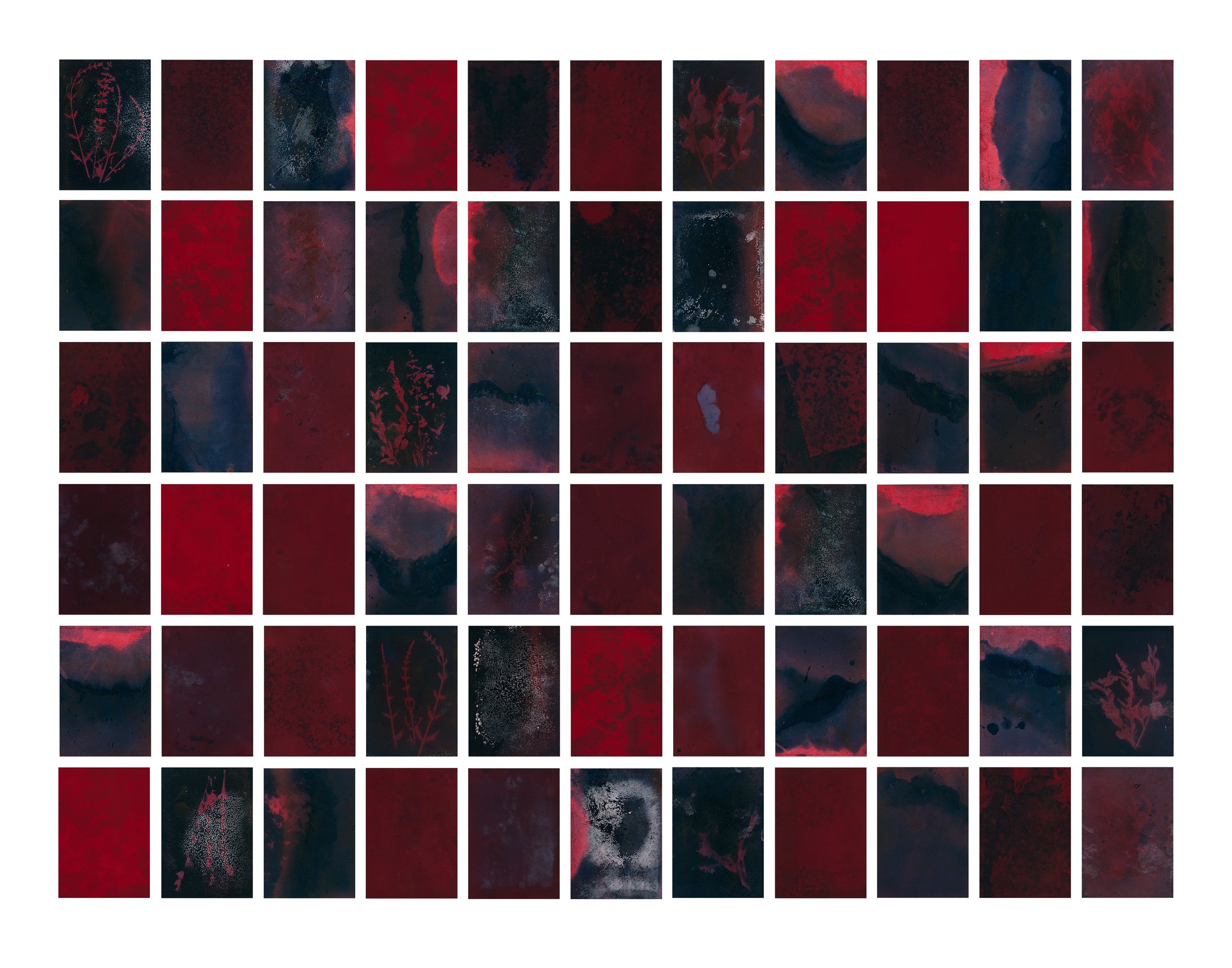

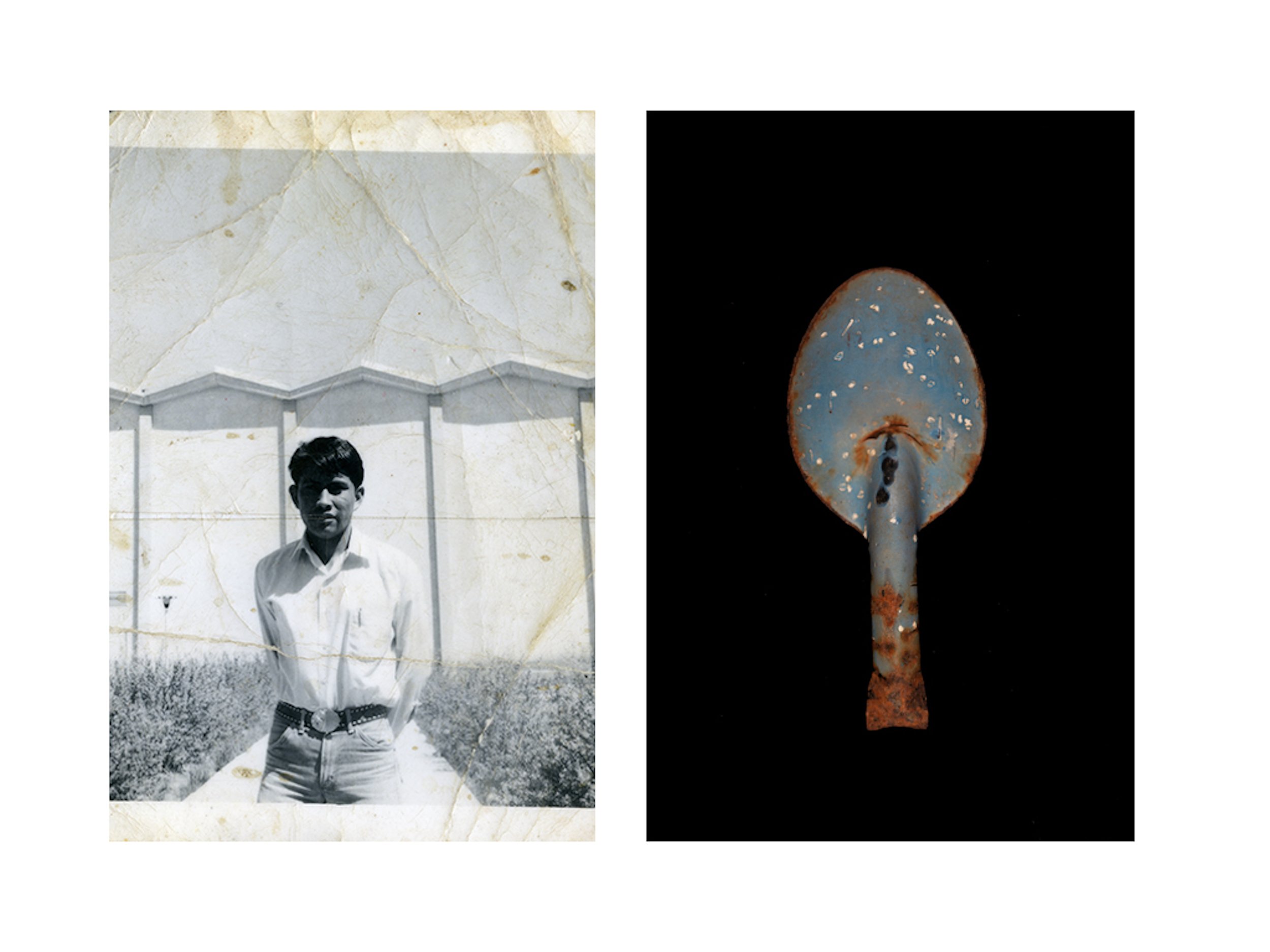

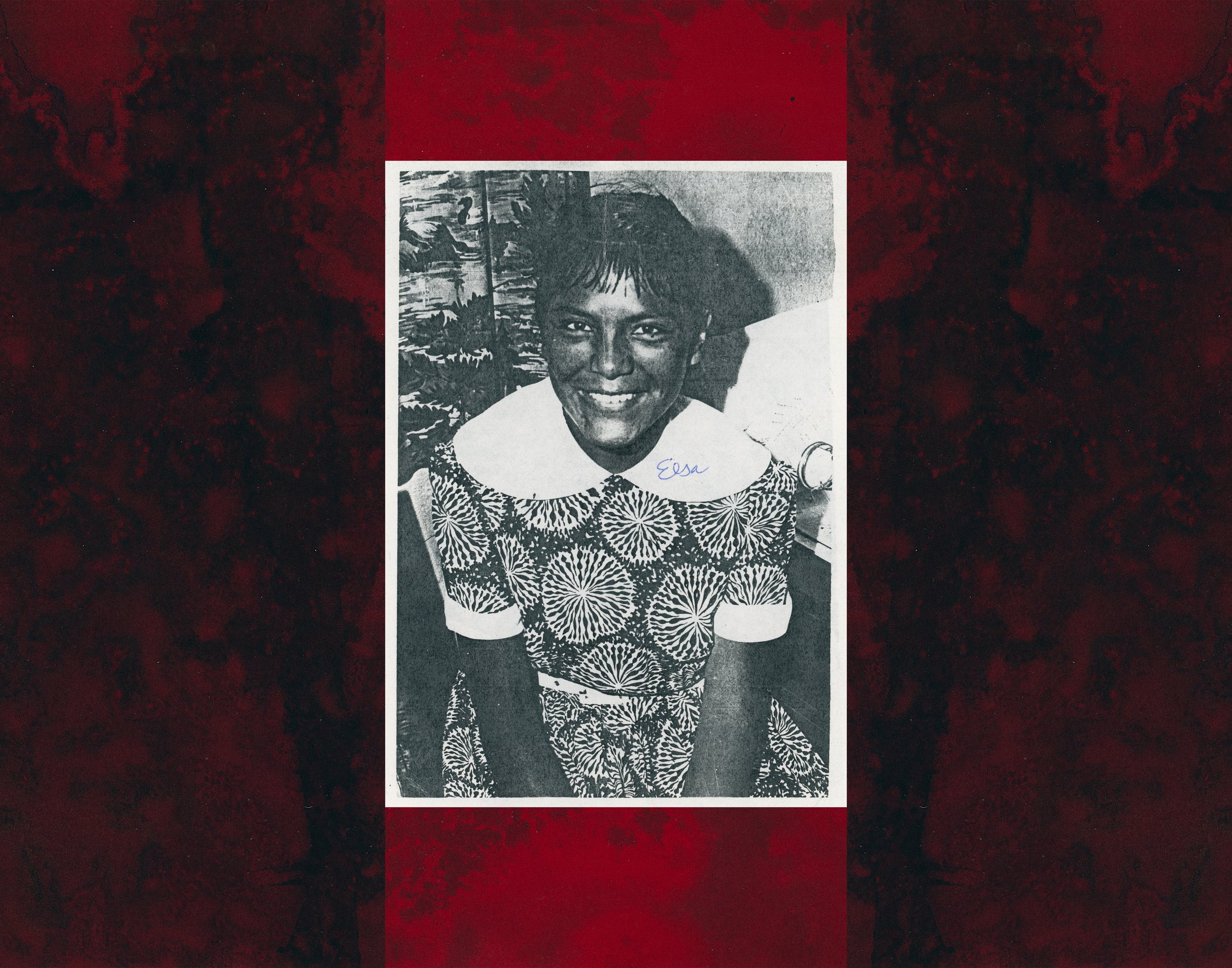

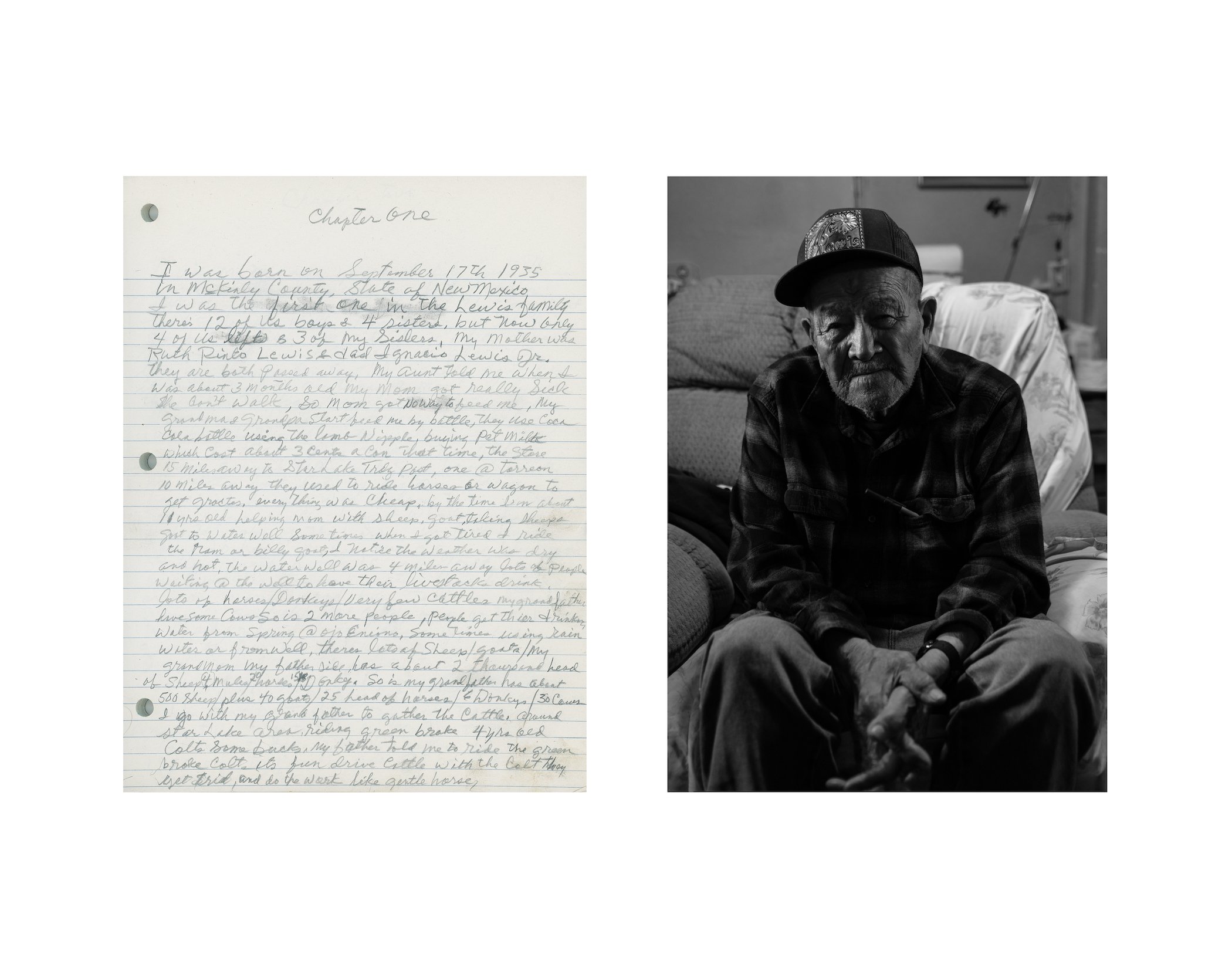

Hwéeldi (Bosque Redondo) is the site that was the final stop in what was known as the Long Walk for the Diné, a painful removal of my ancestors from their home. Hwéeldi is the Diné name for Fort Sumner, located in central New Mexico. It is a place of extreme hardship where many of my Diné ancestors were imprisoned from 1864 to 1868. During this period, many Diné perished and were unable to return to their home, and the only existing photographs erased our identity, romanticizing our pain. The stories remembered come from the elders, where each story was passed on from generation to generation. Many of these stories and the history of Hwéeldi were omitted from U.S. history books, furthering the effects of colonialism. While the stories existed, many elders chose not to tell these stories, believing that further harm could come from these memories. This project provides the platform for carefully using photography and oral narratives to offer healing for those who came before us and future generations.

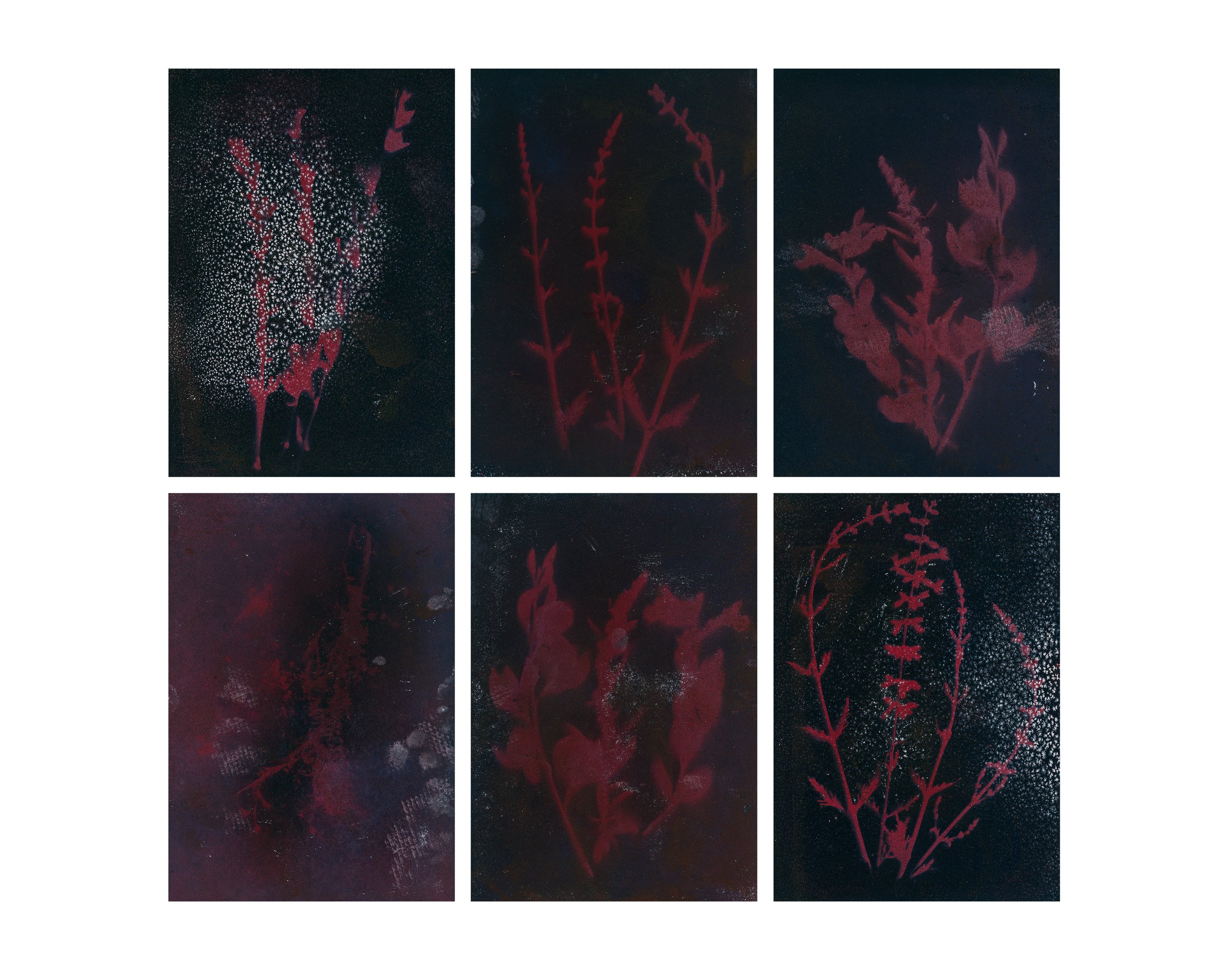

While the stories of Hwéeldi are withheld, and responses to such death and violence are not to be taken lightly, there is a need to carry these stories of resilience. Each photograph represents the lost stories of our ancestors who don't exist in the minimal records kept within Fort Sumner. Like the effects of COVID-19, many lost individuals are only represented by numbers. Our stories allow us to see our history as a continuum of our traditions and culture. While the Long Walk to Hwéeldi happened more than a hundred years ago, it is still with us, and we must remember what happened. This has held true to our current situation of COVID-19 and the second most significant loss of Diné life. Through the memories of our home, we persevered and continued our traditions and stories. This moment in our history defined a new era of sovereignty, one of resilience and survival, and reminds us of the struggles for the rights of our land, natural resources, and freedom.

It wasn't until the passing of the American Indian Religious Freedom Act in 1978 that my own people were allowed the freedom to practice our ceremonies, collect sacred materials, and visit our sacred sites that have existed long before the birth of our nation. This is just one reminder of how very recently the freedom of spiritual practices of the Americas' Indigenous people were allowed and the trauma that resulted from it. Through the camera, traditionally seen as an oppressive weapon, I challenge documentation of Indigenous people by decolonizing the violent visual history of colonialism. Through my work, I provide the opportunity to heal and allow the land and its natural materials to tell our stories.

Dakota Mace is member of the Diné (Navajo) people working as an interdisciplinary artist who focuses on translating the language of Diné history and beliefs. Her work draws from the history of her Diné heritage, exploring the themes of family lineage, community, and identity. In addition, her work pushes the viewer's understanding of Diné culture through alternative photography techniques, weaving, beadwork, and papermaking. Follow her on Instagram @dmaceart.

This is one of eight stories from The Past Is Present project, a collaboration between National Geographic and For Freedoms.